Concussion Management

What the research says about concussion management

Learn about how this head injury is managed.

What is The Concussion in Sport Group

The Concussion in Sport Group (CISG) is a panel of concussion experts who put together a concussion consensus statement regarding sport-related concussion (SRC) for health care providers treating athletes. 1 The Berlin Consensus Statement is the most recent consensus statement from 2016, which is generally updated every four years. It was not completed in 2020 due to the global pandemic. The consensus statement provides recommendations for complete SRC management including identification, removal from play, evaluation, rehabilitation, recovery, return to play and prevention.(1)

What is a sport related concussion?

“Sport related concussion (SRC) is a traumatic brain injury induced by biomechanical force” (1). SRC mechanism is by a direct blow to the head or any part of the body which transmits an impulsive force to the head (1). SRC are a type of mild traumatic brain injury, with an estimated 1.6 to 3.8 million cases occurring annually in the United States (2). Exact incidence is unknown as athletes regularly underreport their symptoms, due to lack of recognition or desire to continue playing (2). SRCs may be more common in females than males in similar sports (3). Concussions are also 6 times more likely during organized sport than during leisure physical activity (4).

How do I know if I have a concussion?

Symptoms are rapid onset of impairment of neurological function, which resolve spontaneously, reflective of a functional disturbance rather than a structural disturbance (1). Signs and symptoms of SRC include somatic, cognitive, and emotional symptoms, balance impairment, behavioural changes, cognitive impairment and sleep/wake disturbances (1).

The most common symptoms are headache and dizziness (2). If any one or more of these symptoms begin after a plausible mechanism, a SRC should be suspected (1). The athlete should be observed for several hours post-injury for monitoring of deterioration of symptoms (2). If a patient experiences repeated vomiting, severe headache, seizure, slurred speech, numbness or weakness in extremities, unusual behaviour or any signs suggestive of basilar skull fracture such as Battle sign or raccoon eyes (2).

What tests are used to diagnose concussions?

At this time there are no definitive diagnostic tests or markers to diagnose SRC, and therefore anyone with suspected SRC should be sidelined and assessed (1). Neuroimaging is not considered diagnostic as it cannot diagnose SRC, however it can rule out more serious traumatic brain injuries (2). The consensus statement has identified advanced neuroimaging, fluid biomarkers and genetic testing as possible future tools for clinical assessment, however still require more research to be validated (1).

The recommended side-line evaluation tool most widely used is the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5), which is not used to determine a definitive diagnosis, but as an initial screening before a more throughout assessment (1). The SCAT5 has multiple components including symptom evaluation, immediate memory, concentration, neurological screen, mBESS and delayed recall (5). These subgroups were examined by using the SCAT5 on professional hockey players from the NHL over the course of the season when there was a suspected concussion (5).

How accurate is the SCAT5?

The subcomponents were assessed to see if they were accurate for differentiating concussed players versus controls (5). The study found that symptom reporting, immediate memory and delayed recall tasks all sufficiently differentiated concussed hockey players from controls, while concentration tasks did not add independent value (5). Continued evaluation of the role of subcategories of the SCAT5 will help better validate its usefulness as a sideline assessment tool.

Regardless of the outcomes of the SCAT5, no athletes should return to play until fully assessed by a trained health care professional (2). A full examination includes a thorough history and neurological exam, including assessment of mental status, cognitive function, sleep/wake disturbance, vestibular function, ocular function, gait and balance (1).

A neuropsychological assessment is important as although cognitive recovery often aligns with symptomatic recovery, cognitive recovery can also be delayed (1). Although neuropsychological findings should not dictate recovery alone, they can inform return-to-play decisions (1).

What should you do after a concussion?

A brief period of rest is often the first prescribed stage of recovery, for the first 24-48 hours after injury, to decrease energy demands on the brain (1). It was previously believed that patients should ensure absolute rest until all symptoms had resolved, however recent research indicates complete rest beyond this initial period may lead to poorer recovery outcomes (6).

Patients should then be strongly encouraged to return to activity while remaining below a level of exacerbating their cognitive and physical symtpoms (1). Since SRC can have concurrent injury to the peripheral vestibular system and cervical spine, a multidimensional rehabilitation approach including psychological, cervical and vestibular rehabilitation is supported (1).

A prescribed and monitored active rehabilitation program to safely return to activity while remaining under a symptomatic threshold, is recommended as beneficial for facilitating recovery (1). Research has also found that sub-symptomatic threshold aerobic exercise in particular may promote faster recovery (6).

A large majority of athletes recover within the first month post-injury, however many continue to report symptoms for months longer (1). There have been many studies which have tried to identify pre-injury factors which may cause a patient to experience more negative symptoms or a longer duration of symptoms, without much conclusion (1). However the strongest predictor of slower recovery is the severity of a person’s initial symptoms within the first few days (1). Development of migraines or depression are also likely risk factors for a longer recovery (1).

What are persistent symptoms of concussions?

Persistent symptoms include any symptoms beyond the expected recovery time frames, over 10-14 days for adults and over 4 weeks for children. 1 Common persistent symptoms include chronic migraines, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, attention problems and sleep dysfunction (1).

What is involved in concussion rehabilitation?

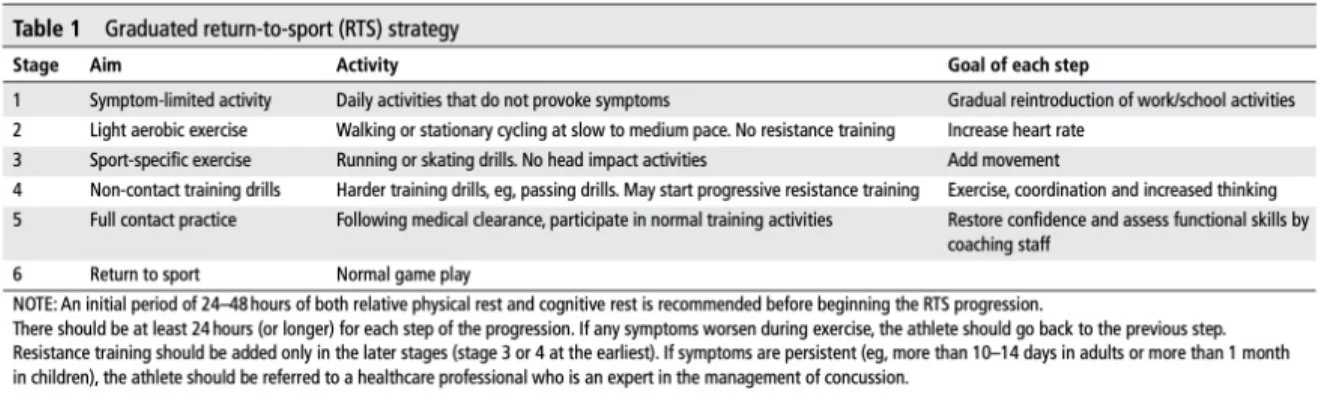

The consensus has a graduated stepwise rehabilitation strategy seen in Table 1 for return to physical activity and sport. The first stage can be attempted after the initial 24–48-hour period of rest. The table outlines what the activity is and the goals of each of the 6 stages.

An athlete can progress onto the next stage once they successfully complete a stage without having exacerbation of any concussion related symptoms for 24 hours after (1). If an athlete does experience symptoms, they must drop down to the previous stage and may only progress again once being successful at that previous stage (1). Therefore the fastest someone can progress through the program is 7 days, however it is not uncommon for it to take longer as it is likely not every stage will take the minimum 24 hours (1).

It is also important for schools to have a return-to-learn program for students to be able to take a graduated approach to increasing their cognitive load (1). The consensus emphasizes that “children and adolescents should not return to sport until they have successfully return to school. However, early introduction of symptom limited-physical activity is appropriate.” (1).

Table 1. Berlin Consensus Statement Graduated return to sport strategy (1).

What can help with preventing concussions?

The Berlin Consensus Statement also addressed possible SRC prevention strategies that have been investigated (1). There is sufficient evidence for helmets reducing overall head injuries, however its evidence in reducing specifically SRC is limited (1). There is a non-significant trend in the literature regarding the preventative features of mouth guards for SRC (1). There has been some evidence to support policy changes within sport to decease incidence of SRC (1).

The best evidence supports eliminating body checking in youth ice hockey (1). Evidence to suggest that SRC in soccer occur primarily due to high elbows in heading duels, have led to policy changes in professional soccer (1). There is also evidence that limiting contact in youth football has led to decreased head contacts, however this has not yet been found to necessarily limit SRC (1).

As always, more research is required in the field of concussions and SRCs, however much progress has already been made. It is important that as many parties involved are educated on the sign and symptoms, removal from play, and return to play protocols as possible to better identify and managed SRC. These parties include athletes, coaches, parents, administrators, referees and more.

If you or your child have or suspect a concussion visit a health care professional for an assessment. To visit a health care provider at Rehab Hero, you can book in with one of our clinicians in Markham or Toronto by using the button below:

Written by: Dr. Emily Kawaguchi, DC

Dr. Emily is a chiropractor that practices in the heart of North York. Having completed her Masters in Professional Kinesiology, Dr. Emily aims to use the most recent research to provide evidence-based care to her patients.

Resources:

1. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, Aubry M, Bailes J, Broglio S, Cantu RC, Cassidy D, Echemendia RJ, Castellani RJ, Davis GA. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. British journal of sports medicine. 2017 Jun 1;51(11):838-47.

2. DynaMed. Sports-related Concussion. EBSCO Information Services. Accessed November 19, 2021. https://www.dynamed.com/condition/sports-related-concussion

3. Halstead ME, Walter KD. Sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010 Sep 1;126(3):597-615.

4. Meehan WP, Bachur RG. Sport-related concussion. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan 1;123(1):114-23

5. Bruce JM, Thelen J, Meeuwisse W, Hutchison MG, Rizos J, Comper P, Echemendia RJ. Use of the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5) in professional hockey, part 2: which components differentiate concussed and non-concussed players?. British journal of sports medicine. 2021 May 1;55(10):557-65.

6. Seehusen CN, Wilson JC, Walker GA, Reinking SE, Howell DR. More physical activity after concussion is associated with faster return to play among adolescents. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021 Jan;18(14):7373

7. CCGI. Clinician Summary - mTBI. Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative. [cited 2021 November 19]. Available from: https://5fd9fdec-587d-4499-9f32-a02895f41f3b.filesusr.com/ugd/21ecf4_5c63d166548b45179201b05bf0a17dde.pdf

8. BMJ Best Practice [Internet]. London (UK): British Medical Association. Mild traumatic brain injury. [updated 2019 April; cited 2021 Nov 19]. Available from https://www.cmcc.ca/library/clinical-databases